When I can get away with it, I call myself a phenomenologist with an audio recorder. That is to say I’m immersed in a particular branch of philosophical thought that is concerned with being, and am trained as a journalist and academic oral historian to interview people as a means of exploring the varieties of lived experience.

My lasting fascination with humanistic endeavor across cultures and through time found a taproot in the thoughts of the controversial yet ever intriguing German philosopher Martin Heidegger, who took on the project of considering being in an age of technology. Hearkening back to Nietzsche, he says our sense of our own being in the world is ‘evanescent as vapor’ and that only by asking ourselves an historical question can we ascertain the ‘full and rightful scope’ of our being in the world. For Heidegger, when we orient ourselves toward a historical question, we ‘open up a happening’ in the present moment, ground ourselves in our ‘originary powers’ and historical purpose, and imagine possible futures.

Of course, my favorite Heidegger passages buried deep in Being & Time, Introduction to Metaphysics, and Poetry, Language, Thought don’t have any actual connection to oral history, per se. I quite doubt Heidegger thought of oral history, ever. Yet I have found no better way to describe the magic and disruption of perceptual time that can happen in an oral history interview, where time is fractured and we pause to relate to each other as interesting and interested beings-in-the-world. I am a phenomenological oral historian because I revel in this moment—the experience of the interview— a way of being in the moment in which Heidegger would say we are ‘burdening the present.’

Expediting Experience through the 3-C’s

As a full-time faculty member in a small liberal arts college with a work requirement, I have ample opportunity to consider how we are in the world. I teach in Antioch College’s Cooperative Education program, where students alternate periods of academic study on campus with full-time jobs or research experiences in local or global partnerships. Antioch students spend between one-quarter and one-third of their undergraduate experience “on co-op.” My job is to facilitate that experience for humanities students— through thick advising, asynchronous, synchronous, hybrid and face-to-face teaching, and extreme partnership development on the ground in communities near and far.

Antioch’s ‘Three C’s’ of classroom, co-op, and community have proven to be a curiously enduring framework for immersive and transformative learning since the program was implemented in 1921 by innovative public architect Arthur Morgan. Inspired by the pragmatists (read: Dewey), the idea is that these three pillars form a total package of experience that reliably brings about transformative growth.

The first ‘C’ is met through our gen ed curriculum, where readings and discussions fill students’ minds with ideas and provide foundational knowledge and concepts. The second ‘C’ represents significant direct experience catalyzed through co-op, in which the normal rate of work-world experience for young adults is amplified and expedited through mentored placements in organizations, think tanks, and companies throughout the states and around the world. (There is no doubt that the phenomenological reality of being thrown into the world four or five times throughout the undergraduate experiences is transformative— students comport themselves differently after their first trip out to a new city in which they must find their way through life and through work.) The third ‘C’ is experienced through the laboratory of community governance, through living together and struggling to build right relationships and governance structures capable of stewarding an ever-emergent vision of campus life.

The transformative nature of our program is undeniable. Students come back from co-op different, as they have for 95 years. As I see it, co-op expedites life, and as co-op faculty I find ways to facilitate this process (and stay out of its way).

Experiential Learning: Philosophy Needs Pedagogy

‘Experiential learning’ became a buzz-word and general mandate on our campus in recent years (as it has on most small liberal arts campuses), and co-op began being referenced as our ‘flagship experiential program’. While I admit basking in the faint glow of recognition for being aligned with The Next Big Thing, the language didn’t sit well with me. I think it threatens to obscure an important distinction— experiential learning is more of a guiding philosophy than it is a pedagogy in and of itself. I’ve come to believe that we do ourselves a disservice when we conflate educational philosophy with tactical strategy, or point to programs when we mean to identify pedagogy.

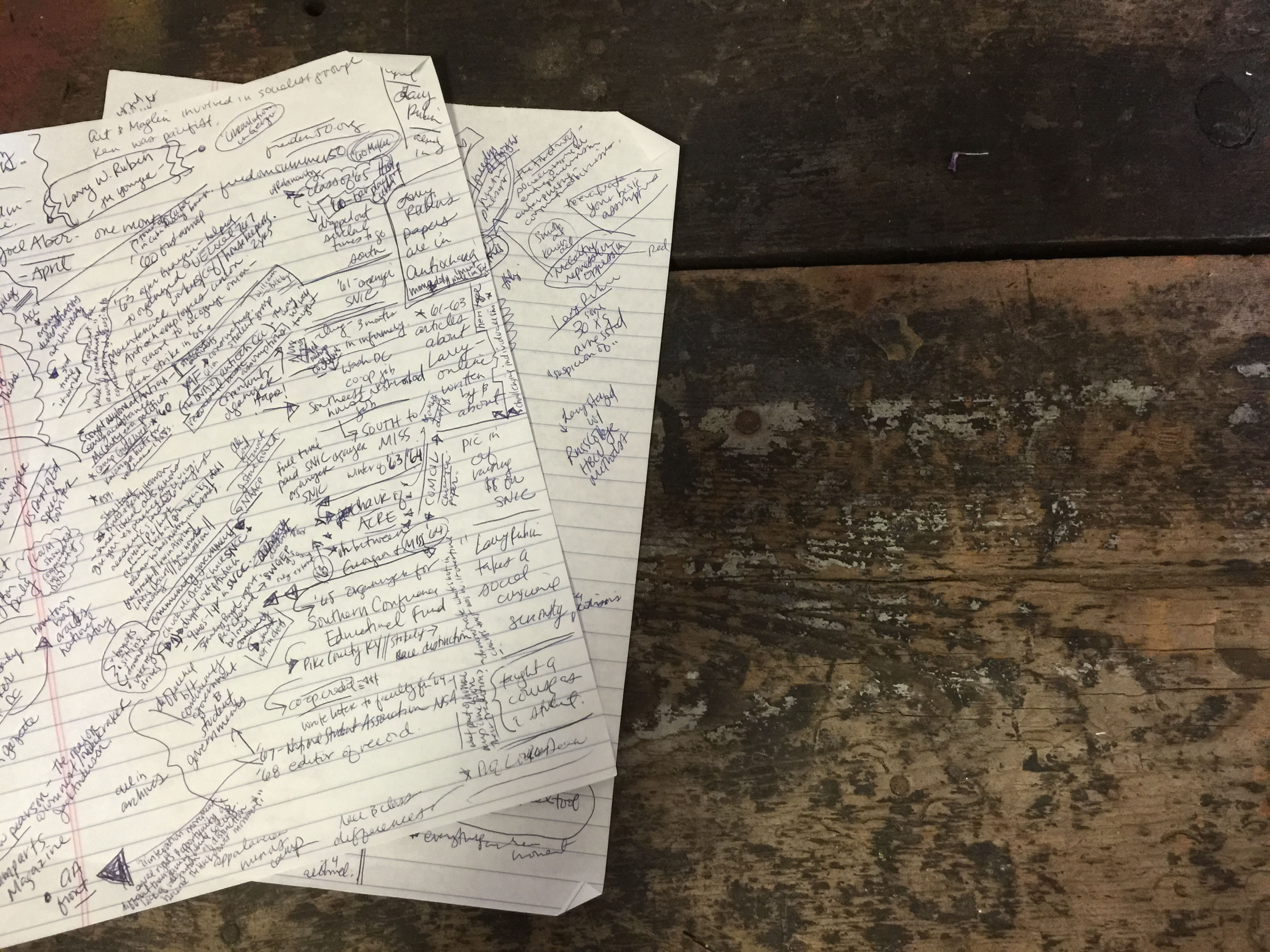

So, my engagement with OHLA is an attempt to wrestle pedagogy into my program by articulating a set of methods and teaching strategies that are reliably grounded in humanistic inquiry and readily capable of animating our liberal arts learning outcomes. I’m thinking about students engaged in community-based learning with audio recording gear, asking carefully-formulated questions stemming from their faculty mentor’s curricula. I’m thinking about a sort of learning that is deeply grounded in experiential learning philosophy because the learning happens through direct, phenomenological experience when students sit next to someone, look them in the eyes, and listen. (I mean listen, where listening becomes an immersive lived experience.) I would argue that this level of listening is a being-with or a being-towards that often leads to a transformative encounter with the other— an experience that allows the nuance and particularity of another’s perspective and personhood to reveal itself. This being-with can be a sweetly magical experience or disorienting and troubling.

This sort of learning requires that students be immersed in the ethical considerations of informed consent— to know what it is to be a free agent in the world who can choose to speak about things that are sometimes difficult to speak about— and who can also choose to stop speaking or to control what is shared from what was spoken.

This sort of learning requires meaningful relationships with community partners, and an institutional commitment to stewarding the embedded, intersectional, and nuanced nature of ideas that our students capture with digital media.

This sort of learning requires that students be trained in tactical interview methods and a basic command of a few digital tools to aid in catching stories and sharing their themes with the communities from which they arise.

This sort of learning is ‘high impact,’ integrative and transformative.

My end hope for the model OHLA is testing and building will speak to people who would never consider themselves ‘oral historians’ or ‘digital storytellers.’ I hope that the driving questions that power student fieldwork and inspire community partnerships come from the curriculum, and that the outcomes of the fieldwork (digital projects featuring navigable, media-rich narratives) are published and brought back to campus from the field. I also hope that these projects, these growing archives, are used as open educational records (OER) in successive classes, becoming a tap root of the disciplinary culture of learning that is truly informed by lived experience (and, sometimes, transformed by it).

This is a liberal sort of learning.